The need for artful science

The greatest scientists are artists as well - Albert Einstein

Human Science will discuss this topic and video in an upcoming Clubhouse room. Join the conversation at joinclubhouse.com/club/human-science and reach out to @husclub to learn more. Subscribe to Human Science to stay informed about additional audio and livestream events.

Background: This Anthropological Life

I recently found myself talking about what I feel is the connection between art and science during an interview for This Anthro Life podcast. I was asked why I became an anthropologist and, because I expected the question, planned to talk about moving around as a child, facing nearly constant culture shock, and becoming interested in how people did things differently whenever I moved to a new place. But my interviewers approached this topic in an unexpected way and I found myself discussing art and science. I wanted to share some thoughts on this, especially in light of a Wenner-Gren Foundation project that I’m working on with a small group of anthropologists focused on public intellectualism.

I was an artsy child and attended high school at at Interlochen Arts Academy. Although I was a creative writing major, I was primarily interested in why art had meaning across media and disciplines, like visual art, music, and writing. So in college, I pursued a self designed a major called Semiology of Visual Culture. This concentration focused on understanding how symbolic communication worked, essentially trying to understand the social and behavioral science behind art and human expression. As a result of becoming more interested in how and why people communicated artistically than making art myself, I switched my career focus from writing, film, and advertising to cultural anthropology. However, I did this with the goal of eventually applying what I would learn to industry.

Now, my focus has shifted from the science of art to the art of science and public intellectualism. To be impactful beyond their disciplinary silos, scientists have to put as much thought into how they express themselves as artists. And, while academia generally doesn’t incentivize public engagement very much, the pandemic and social unrest of 2020 has brought many scientists and experts out of their silos. Society needs scientific expertise more than ever… and many experts are heeding the call.

Unfortunately, scientists and other experts often have difficulty influencing public opinion, even about their specific areas of expertise. Public discourse often stays at the basic level of arguing about whether insights from scientists and experts are even worth discussing. So, even as humans face the dramatic consequences of climate change, a global pandemic, and systemic racism, the general public is often debating their very existence. While there is intellectual diversity among the experts addressing these issues, most people in society don’t bother themselves with them. But the problems academics find and discuss, through problematizing, have real world implications that business and political leaders encounter and do their best solve everyday. This is illustrated through the rise of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns alongside the growth of anthropology in industry.

Scientists often collaborate with experts outside of their silos in ways that are white-labeled… hidden in plain sight with the contribution of the sciences, including behavioral and social science, remaining unacknowledged to the public. And the COVID-19 Pandemic has revealed how the impact of experts on public discourse has declined in the social media era. I think a crucial part of how experts (i.e. public intellectuals) can make their comeback lies in them leveraging emerging media formats, like drop-in audio, and learning how to express their understanding of the world to audiences outside of their silos more artfully.

The following essay is available through audio narration in the video above.

Influence & Expertise

For any topic that’s being discussed by the general public, I think about the most notable people talking about it as falling into one of two general categories: influencers and subject matter experts.

But there are also two intermediate categories. One is thought leaders, which is a segment that has become increasingly prominent over the last decade with the help of platforms like TED talks and the emergence of thought leadership marketing in industry. Thought leaders are influencers, but they can speak with authority about issues because of their knowledge about them. A fourth category, public intellectuals, receives much less attention from the public nowadays. They are experts who are able to engage an audience outside of their professional communities, which generate the knowledge they’re sharing.

Influencers

Influencers often come from the arts and entertainment, but in many ways we all fall into this category on some level in the age of social media. Social platforms allow us to express ourselves and influence each other in new ways. Influencers discuss what’s happening in the world and, in doing so, spread awareness about issues and current events. But they also shape people’s opinions, not so much because of what they know but who they are, the size of their following, and how well they express themselves. Technological change now allows us to be influenced by more sorts of people, more of the time, in more ways than ever. Influencers bring to bear their ability to express themselves in order to create content that engages a public audience. And they’re usually effective at leveraging short-form and image-based social platforms, which have grown in popularity over the last decade.

Subject Matter Experts

On the other side, there are subject matter experts. They are able to impact society, but it’s because of what they know instead of who they are. They tend to work behind the scenes and seldom impact public discourse very noticeably. Subject matter experts are members of communities that generate new knowledge. This means that they don’t just have knowledge about their topics, but they also have the skills required to help produce it.

Thought Leaders

Thought leaders create content and share ideas like influencers, but it’s based on some authority they have when it comes to a certain topic. They don’t have to be subject matter experts, but they often synthesize or explain the ideas of experts in ways that are more assessable to broader audiences. Their focus is creating content and proposing intriguing ideas based on their insights and this often incorporates the work of experts in relevant areas. But what they share is also going to be shaped by their personal biases.

Thought leaders tend to come from journalism and business, domains that often translate theories and concepts from the arts and sciences for broader audiences in the general public and business.

Public Intellectuals

Although they're often associated with academia, public intellectuals can come from anywhere. They explore their areas of expertise critically, as experts, but also engage broader audiences. Thought leaders are oriented towards creating interesting ideas that tend to be associated with them as individuals. While they’re often evangelizing them as new inventions, public intellectuals are more oriented towards an analytical understanding of issues and are more likely to evangelize their domains of expertise.

Expression & Understanding

People often move across these categories throughout different career stages. As examples, let’s talk about two well known people in science, Bill Nye and Michio Kaku. Although they have similarities, they have very different backgrounds and skillsets. Bill Nye has a bachelors degree in mechanical engineering, but throughout his career he’s been focused on writing and entertaining people by explaining scientific ideas. Early in his career, he created content for children as a TV personality. But over the years his influence has grown alongside his understanding of the topics he discusses and the breadth of his audience. Now he’s a thought leader on topics like climate change because of the credibility he’s gained over decades as a science guy… even though he isn’t a scientist.

Dr. Kaku as a high school student with a small particle accelerator... that he built

Michio Kaku, on the other hand, is a theoretical physicist. He has deep scientific expertise and as his career has evolved, he’s become more effective at expressing his ideas as a writer and orator to the point of becoming a public intellectual. He can contribute to the actual work of scientists in ways that Bill Nye can’t. But both of them can contribute to the public’s understanding of science through their content and, in the area of science communication, they both have significant expertise. So if an organization wanted advice on how to impact society’s scientific literacy, they’d both have meaningful expertise to offer. And there are people who eat, breathe, and sleep science communication who have even more expertise in this area and work behind the scenes in academia and entertainment.

Nye and Kaku demonstrate how creative expression can elevate the work of experts, and this is something that we can see by looking at other prominent figures from the arts and sciences.

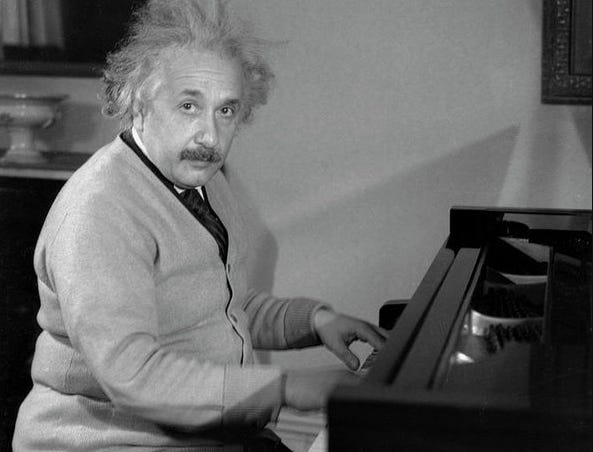

Albert Einstein is perhaps the most influential public intellectual of the 20th century because of his work as a scientist, but he would play piano and violin as he thought through his theories.

Live Aid in 1985

And David Bowie isn’t the only legendary rock star who’s associated with stardust, because Brian May — the guitarist for Queen who wrote hits like We Will Rock You — is also an astrophysicist who did his doctoral research on zodiacal dust. And two of the most culturally impactful filmmakers of the 20th century, Orson Welles and George Lucas, share a reverence for cultural anthropology. It makes sense that a discipline focused on understanding the human experience might inspire artists who portray it, even when their characters aren’t human.

I began to fully appreciate the difference and interconnectedness of art and science after a conversation with a guitarist a few years ago.

Train of Thought

In the summer of 2016, I was teaching cultural anthropology to high school students in Harlem. I had to take the subway to a meeting across town, which took between one and a half and two hours each way. It was a hot day and I had just started a very demanding job in Big Tech. The pay for the teaching job was negligible and I didn’t understand why this administrative meeting had to be in-person. I was in a bad mood and began to question my decision to take on this additional job that was more difficult and stressful than the one I was using to pay my bills. As I waited for the train, a musician who looked to be in his 50s came up to me and started asking me questions about my educational background and what I did as an anthropologist. Once our train arrived, we sat together and started talking about our lives. We learned that we had lived in some of the same areas of the US along the Gulf Coast, in Texas, Mississippi, and the Florida Panhandle. Then he asked me a question I didn’t expect.

“How do you deal with negativity?”

I asked him to clarify what he meant and he began talking about his insecurity about not having much formal education, making his living by busking, and wondering what educated, affluent, and white people thought when they saw him… until he starts playing his guitar and all his insecurities fade away. As he spoke, I began to realize this was his artful way of asking me how I, as someone who could relate to some of his experiences as a black man in America, dealt with racism.

This was something I’d never thought about before, so I began trying to explain.

I guess I always tried to understand why… what was going on…

And then he excitedly said

“Analyzing!”

He remarked on how interesting it was that he coped with his hardships by expressing himself as an artist but I dealt with mine by trying to understand them through science. And we talked about my students, who were constantly reminded of the privileges and resources they didn’t have while they dealt with an increasingly uncertain world as Black Lives Matter entered the public consciousness and Trump emerged as a political leader. Once we talked through his insight as co-theorists, but with him taking the lead, he said

And that’s what you’re doing for those kids.

Shortly after, we thanked each other for a great conversation as we arrived at his stop. As he stepped off the train, he said

Thanks for talking with me. I learned a lot from you.

For the rest of the train ride, I reflected on what is to this day is the best interview I’ve ever seen, and it was conducted by an artist who turned me into the anthropological subject.

This 20-minute conversation helped me realize:

I’m an anthropologist because it’s in my nature to cope with my existence by trying to understand it better.

This compelled me to teach anthropology to students of color in high school. I wanted them to be able to make some sense of a society that was getting crazier by the day.

And people try to make sense of the human experience by expressing it as artists as well as understanding it as scientists.

In the span of our short conversation, an artist who didn’t know what anthropologists did before striking up a conversation with me revealed himself to be one of the most talented I’d ever seen. And I reflected on this as I continued uptown with a new sense of purpose.

So expression and understanding have a natural tendency to reinforce each other and, as a result, great artists and scientists tend to be one and the same. And although there are clear differences between thought leaders and public intellectuals, the best of both find ways to work at the intersection of art and science — expression and understanding.

Dunning-Kruger & Epistemic Trespassing

It’s no surprise that as 2020 brought a global pandemic alongside widespread social unrest, experts and public intellectuals have tried to raise their voices to help make sense of the world.

Among the most culturally relevant nowadays are psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, known for discovering the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Although they offer fairly clear explanations for what it is as scientists, my favorite comes from John Cleese, an artist.

The Dunning-Kruger effect can explain a lot about the human condition right now, such as why people who lack an understanding of virology or epidemiology confidently disagree with experts like Anthony Fauci about COVID-19 or propose ways to treat it that have no scientific bases. And the related concept of epistemic trespassing, explored by Nathan Ballantyne, explains how some people erroneously believe their expertise in one domain qualifies them as experts in another area.

In fact, epistemic trespassing can be used to great effect for a person’s career. For example, William Happer is a scientist who has deep expertise in adaptive optics, a technology that allows ground-based telescopes to correct for atmospheric turbulence and dramatically improves the quality of images captured by them. He doesn’t think carbon dioxide emissions cause climate change but he also isn’t a climate scientist. However, because he has earned credibility and credentials from his work on optics and pushes a narrative that climate change deniers want validated, he was appointed to leadership roles related to climate science in the US government in 2018 and 2019.

This is important to understand when you see something like a debate between William Happer and Bill Nye about climate change. They are two people who have impacted public discourse related to the topic a great deal, despite neither one of them actually being subject matter experts on the science of it. And they’ve shaped public opinion about climate change more than any climate scientist has. They’re both thought leaders, with Nye promoting a narrative informed by scientific consensus and Happer’s based on his work, which doesn’t explore the interconnected systems that have to be understood to have a valid scientific perspective about climate change. The most qualified scientists often don’t communicate in ways that engage public audiences. And the voices that traditional media elevate tend to be better for entertainment than providing the public with an understanding of issues.

So what about social media, which can keep traditional gatekeepers at bay.

The Role of Social Media

Unfortunately, the far reaching adoption of social media amplifies the societal implications of the Dunning-Kruger Effect and epistemic trespassing. It can allow influential people to spread bad, even dangerous ideas more easily. Public intellectuals can leverage social media effectively for their careers and some use it to impact public discourse in meaningful ways, but this can lead them to align themselves with polemic perspectives and echo chambers online. Although influencers and thought leaders could appear to be better at using social media to shape public discourse, their success largely stems from how social platforms are designed. They often don’t convey nuance very well to large audiences, and this is where experts add the most value to discussions. The Devil is in the details, but learning about them takes time that many people don’t feel like they have when they’re on short form or image based social media. The nuances about the world the way it actually is have to be communicated thoughtfully and artfully to be meaningful to audiences outside of the expert communities studying them. And public intellectuals need to leverage technological tools that allow them to provide insights about issues that aren’t buried in discussion threads that often get seen by only the most intellectually curious people. And while public audiences may be somewhat inclined to defer to experts when it comes to issues that are inherently political and technical, like foreign policy, when it comes to more fundamental human science, public intellectuals lack the influence of thought leaders on social media designed to prioritize entertainment over informational value.

Take the topic of race for example, which is one of the most studied in the social, behavioral, and biological sciences. A lot is understood now and there are comprehensive resources available to help the public understand this topic holistically. But when Brett Stephens, a journalist, writes about race in a way that conveys a misunderstanding of it, his ideas are more likely to go viral as they’re enthusiastically received and spread by people who share his biases while another group helps the article trend on social media by discussing the problems with it. Short-form and image based formats in particular allow simplistic narratives and disinformation to get traction over those focused on providing the details necessary for a better understanding of the world.

The Medium is Still the Message

The way discussions take place makes a big difference and some formats are better suited to public intellectuals and subject matter experts than others. For example: take the topic of artificial intelligence. The content conveyed through a TED talk about AI would be very different from a subject matter expert interview about AI. A TED talk would convey intriguing ideas about it that likely wouldn’t require deep expertise to develop or understand. On the other hand, organizations often conduct expert interviews to help understand AI problems or develop AI offerings, but most people in the general public would not want to sit through one. There’s a big difference between helping people understand something to address real-world issues and creating interesting content about it. And some thought leaders are great at inspiring new thinking in areas where they don’t have particularly deep expertise.

TED talks use a format with a thought leader or public intellectual on stage giving their perspective through a monologue. There’s usually no space for criticism from the audience, domain experts challenging ideas broached by the speech, or proposing improvements. However, it is possible to create space for public intellectualism, which benefits from an exchange of ideas between experts.

Over the past 15 years or so, people have been able to use technologies developed by scientists to convince each other to distrust scientists. So, even the most basic scientific facts, like the Earth being round and vaccines being good, are falling out of favor in some circles. And this can seem like an existential threat of social media, exacerbated by automation, through bots and algorithms. Human society desperately needs the revenge of the nerds.

A New Era of Public Intellectualism

Recently, a tweet from MC Hammer about philosophy and science went viral. People were intrigued by his perspective and depth of knowledge about these topics. And I saw this tweet around the time I stumbled into a room on Clubhouse, where he was discussing science and technology development with a room full of experts from different disciplines and industries. Clubhouse is a drop-in audio social media platform, kind of like a live podcast, that has become a bit of a cultural phenomenon. In fact, a cyborg anthropologist named Marcus Anderson often hosts conversations with Hammer on the platform.

Clubhouse differs from other forms of social media because it combines the sheer volume of information that can be shared through audio alongside a design that allows for many participants to contribute to conversations. As a result, it’s appears to be better suited for diverse experts discussing topics in a way that provides the nuance often lost or buried within short-form social media.

This paradigm shift may allow public intellectuals to start shaping public discourse more effectively, but it won’t be easy. It’ll mean embracing new formats like drop-in audio and perhaps even leaving academia if it fails to evolve. No matter the specific discipline, scientists must learn how to express themselves to the general public effectively to be relevant to society. So while it’s important to understand how artists like Hammer learn from and contribute to the work of scientists, it’s imperative that scientists learn from artists and express themselves more artfully.

STS is Science & Technology Studies

I’ve encountered this issue in my own work.

As a grad student from 2007-2010, I studied how a Big Science project picked a site for a telescope that, years after the decision was made, became a massive global controversy. It has huge implications for Hawaiian society and the scientific community, but it’s difficult to talk about as a social scientist because most people in the general public aren’t necessarily interested in hearing about the systemic causes of the controversy. Reductive, often false narratives about Native Hawaiians and scientists tend to get the most traction on short-form social media.

I’m also working on a training program, with backing from the Wenner-Gren Foundation, called Anthropologists on the Public Stage. We’re helping experts in anthropology and related fields learn how to shape public discourse more effectively and will launch our program over the summer.

And lastly, I’m producing content like this alongside online events though an initiative called Human Science. So please like and subscribe if this is the kind of thing you want more of. This is my first essay like this, so they’ll definitely get better.

My next one will be about the difference between thought leaders and public intellectuals.

Thanks to Marcia Bartusiak and Mike Wesch for inspiring this essay and the participants of Anthropology on the Public Stage so far: Alfredo Artiles, Astrid Countee, Bob Mierendorf, Bob Morais, Charlie Lehman, Chip Colwell, Cool Anthropology, Dennis Dauble, Dori Tunstall, Ed Liebow, Genevieve Bell, Gillian Tett, Helen Fisher, Jeff Martin, Jim Forrer, Melissa Fisher, Mike Wesch, Paul Durrenberger & Suzan Erem, Paul Stoller, Rebecca Chamberlain-Creanga, Suanna Selby Crowley, Tim Malefyt, and Yolanda Moses.